Deep Dive: Quinine

Add some drug to your drug

I write a cocktail newsletter, which means I spend a lot of time technically looking at drugs (alcohol). But, even so, I can’t claim that this newsletter has taken me to the Mayo Clinic’s website until now. I promised that I’d dive deeper into quinine, and that’s exactly what I’m here to do today.

I’m Obviously Not a Doctor

This newsletter will be talking about a drug that you may have a bad reaction to, and I hope you won’t yell at me if after reading this and chugging a liter of tonic water you don’t feel good. I can’t find any reference that suggests the amount of quinine in tonic water is any kind of risk for bad interactions, but fact remains that in prescription dosage this stuff can be bad news depending on what you take. Be smart, folks.

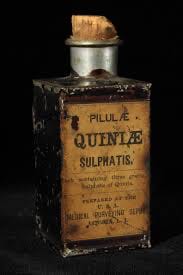

Quinine As a Drug

Quinine treats malaria, and it’s done so for centuries. Specifically, it targets the parasite that gets into red blood cells and causes malaria. It’s had many colloquial uses, most well-known of which is treating leg cramps, but the science doesn’t support any actual use aside from helping to cure malaria and other things very similar to malaria.

Getting it Out of the Tree

Quinine comes from the bark of cinchona trees, a flowering tree native to the tropical forests in the Andes. Indigenous peoples, specifically the Quechua, new of their value, and they used it explicitly to treat patients that were shivering (which is often caused by malaria where the disease is endemic) because of its properties as a muscle relaxant.

At least as early is the mid-1500s and likely centuries earlier, these folks were taking the bark off the tree, grinding it up, and mixing it with sugar water to deliver the drug in a palatable format. It likely tasted a lot like the tonic water of today, and they recognized the bark was too bitter to choke down on its own. When the Spanish invaded the region, they took note of this medicinal use and returned to Europe with bark and seeds.

Foremost among these was Agostino Salumbrino, a Jesuit (so not quite a monk, but if you’re noticing a theme in recent additions of this newsletter your’e not alone: Catholics created a whole lot of modern, western drinking culture), was an apothecary in Lima circa 1600 who took special note of the use of the bark to treat shivering. Rome was suffering a malaria outbreak at the time, and Salumbrino was quick to send bark back to the Vatican to test it as a possible treatment. It worked, and “Jesuit’s bark” became a key piece of intercontinental trade.

The trees became knows as fever trees since the bark treated shivering folks (and now you know where the brand name comes from). But, they only grow at elevation so cultivation in Europe was unsuccessful and the bark itself needed to be transported on ships.

Modern Delivery

For at least 100 years, Europeans didn’t know exactly what in the bark made it an effective malaria treatment and they kept consuming it as a bark powder mixed into liquid (often wine). That first issue seems to have been solved by the stereotypical gentleman adventurer Charles Marie de La Condamine who apparently took money he scammed the French lottery out of (in a scheme he cooked up with Voltaire) to travel South America and actually learn some useful information. That included identifying, but not isolating, the drug that mattered in the cinchona bark and effectively discovering rubber for Europe. NEED a TV show about this guy, preferably similar in vibe to Our Flag Means Death.

Once the drug was identified, it still took about another 100 years to actually isolate it. The French scientists who did that are the ones who actually named it, and they went with quinine because it sounds like the Quechua word for the bark: quina.

Finally isolated, Europeans no longer had to consume bark powder and could make the stuff much more efficiently. Unfortunately, large-scale quinine production in 1850 also opened up Africa to European conquest now that malaria risk was drastically decreased. That’s the dark history here: malaria inadvertently kept some cultures “safe” from colonization, and treatment for the disease rendered that last protection useless.

Tonic Water

The isolated quinine powder was probably even more bitter than the bark powder of previous generations, and soldiers prescribed the stuff needed a delivery mechanism. That most commonly included pure soda and sugar, which yielded the bitter, carbonated tonic water we still drink today. This caught on quick: mass production of the drug started in 1850, and by 1858 there was a patent pending for the first commercial production of tonic water.

This stuff would have been much more bitter than what we have today; after all, this was truly built as a drug, not as a cocktail mixer. As actual quinine tablets became more common and available, the amount included in the bottled tonic waters decreased over time. The tonic water we drink today in the states has, at most, 20% of the quinine content that an actual therapeutic would have contained. Said another way: today’s bottled tonic waters will not protect you from malaria unless you’re absolutely housing them.

Adding Gin

This, too, did not take long. British soldiers in India were prescribed quinine, delivered to them in tonic water. They were also rationed gin. The tonic water was extremely bitter, but adding in booze made it a bit easier to drink and, hey, 2 birds one stone. By 1868, the gin & tonic was being written about as a cocktail to enjoy at a horse race.

Other Additions

While tonic water is certainly the most famous delivery mechanism for quinine, and the gin & tonic has distinctly British origins, this is far from the only cultural addition of quinine into booze.

We’ve already discussed Bonal at length, but quinine is also included in: Dubonnet (another French aperitif that drinks a lot like vermouth), Malaga Wine (a sweetened Spanish wine), and Barolo Chianto (an Italian aperitif also similar in many ways to vermouth). These likely stem from the early penchant of Europeans to drink the bark powder mixed into wine.

Quinine is also added to other bottled beverages aside from tonic. A personal favorite is Bitter Lemon, which is essentially tonic water with a bunch of lemon juice and peel added that tastes like what I want Sprite to taste like. I discovered it in Tanzania, under the Krest brand, and I really wish I could find that at home. Fever-Tree makes one, but it’s not the same…

Summary

Quinine isn’t necessarily the kind of ingredient I had in mind when I started MI, but this has resulted in exactly the kind of deep dive I hoped I would produce here. We have indigenous history, massive political impact, execution across cultures, and a full cast of characters with their own interesting stories. Hopefully, that makes you think a bit the next time you order or make a G&T, or, even better, the next time you mix with your bottle of Bonal.